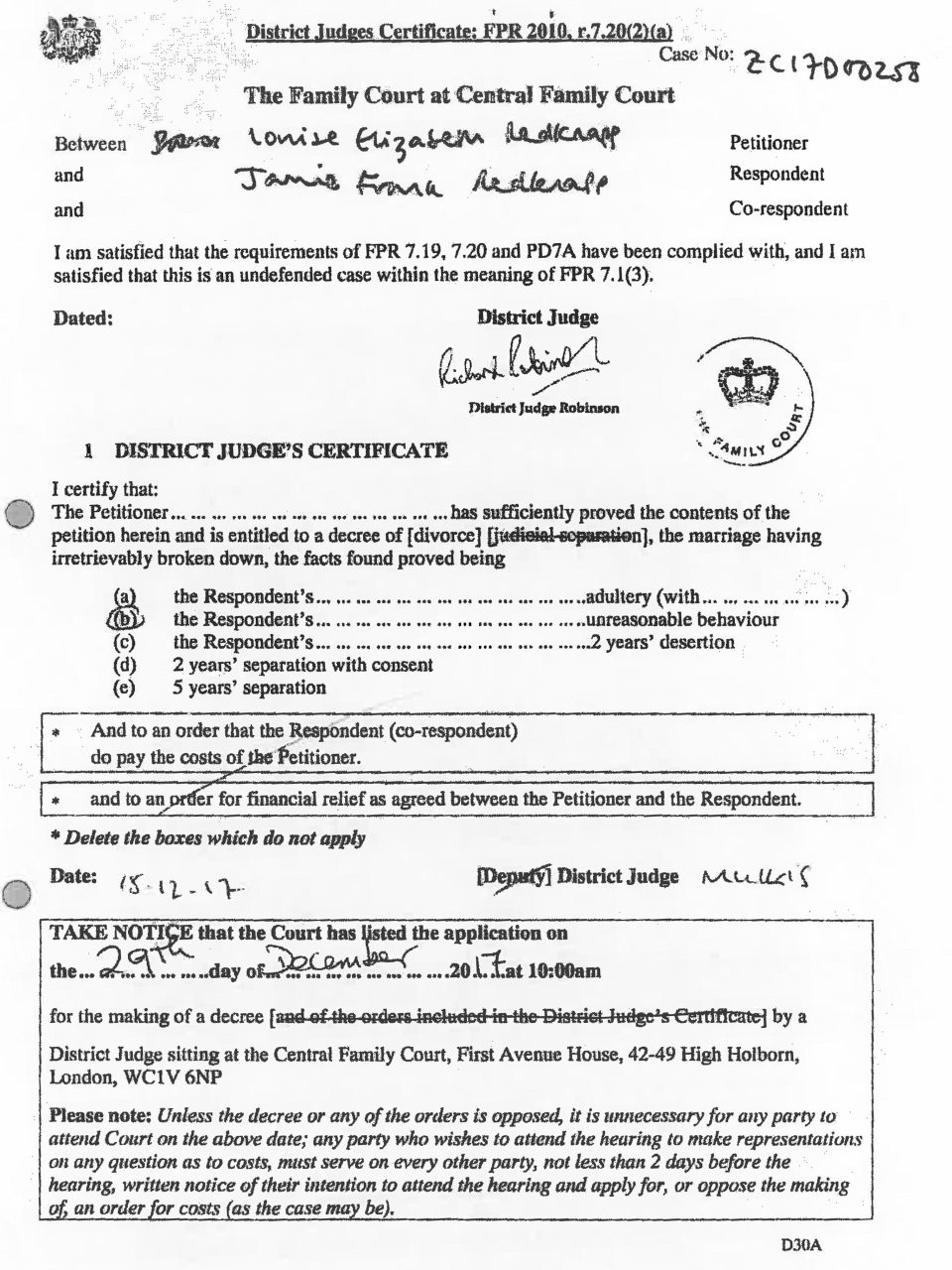

“Judge Mulkis held that Mr Redknapp had behaved in such a way that Mrs Redknapp could not "reasonably be expected" to live with him.”

"The Quickie"

This week Jamie and Louise Redknapps' 19 year marriage came to an end when a judge in London granted the pair a decree nisi. Court documents say Louise, 43, blamed 44-year-old Jamie's "unreasonable behaviour" - The Sun

One of the main differences between divorce law in England and Ireland is the availability in the former jurisdiction of an immediate – or “quickie” – divorce. However, to obtain such a divorce, one is required to demonstrate adultery, desertion or “unreasonable behaviour” on the part of one’s spouse. In other words, in order to get a divorce in England and Wales – in the absence of separation or desertion for certain defined periods – someone must be shown to have been at fault. A divorcing couple, whether they like it or not, has to play the blame game.

In cases like that of the Redknapps in which “unreasonable behaviour” is alleged, the Petitioner (the person who brings the application) must demonstrate that the Respondent (their spouse) has behaved in such a way that the Petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with them.

The Petitioner is required to give examples of this “unreasonable behaviour”. The result of this is that often, in the absence of immediate and serious issues where one party is clearly at fault but where the Petitioner nevertheless wants a divorce without delay, certain problems that might be expected within the normal range of ups and downs of any marriage – from genuine differences about money or domestic arrangements or the rearing of children, to bad manners, to lack of consideration, and so on – are burnished up or improved upon to better fit within the category of “unreasonable behaviour”.

Not only that, it seems that the obligation to attribute “fault” under English law often involves a husband and wife colluding in the creation of various fictional or quasi-fictional misdemeanors – with one of them making a series of allegations and the other tacitly accepting blame – in order to secure the immediate divorce that, in most cases, both of them want.

The process goes so far as to involve the parties’ lawyers exchanging drafts of proposed catalogues of transgressions with the intention of producing a list of offences sufficiently serious to convince a court of unreasonable behaviour but not so egregious that it makes it too difficult for the “guilty” party to acquiesce in the tarnishing of their own reputation.

In the recent English case of Owens v Owens, Sir James Munby in the Court of Appeal expressed the view that this situation, a consequence of the legal requirement to attribute blame, was based on “hypocrisy and lack of intellectual honesty”. Sir James indicated his support for a change in the law and the introduction of a no-fault system, adding his voice to a growing campaign which may see legislation introduced in the UK parliament in due course.

One of the main differences between divorce law in England and Ireland is the availability in the former jurisdiction of an immediate – or “quickie” – divorce. However, to obtain such a divorce, one is required to demonstrate adultery, desertion or “unreasonable behaviour” on the part of one’s spouse. In other words, in order to get a divorce in England and Wales – in the absence of separation or desertion for certain defined periods – someone must be shown to have been at fault. A divorcing couple, whether they like it or not, has to play the blame game.

In cases like that of the Redknapps in which “unreasonable behaviour” is alleged, the Petitioner (the person who brings the application) must demonstrate that the Respondent (their spouse) has behaved in such a way that the Petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with them.

The Petitioner is required to give examples of this “unreasonable behaviour”. The result of this is that often, in the absence of immediate and serious issues where one party is clearly at fault but where the Petitioner nevertheless wants a divorce without delay, certain problems that might be expected within the normal range of ups and downs of any marriage – from genuine differences about money or domestic arrangements or the rearing of children, to bad manners, to lack of consideration, and so on – are burnished up or improved upon to better fit within the category of “unreasonable behaviour”.

Not only that, it seems that the obligation to attribute “fault” under English law often involves a husband and wife colluding in the creation of various fictional or quasi-fictional misdemeanors – with one of them making a series of allegations and the other tacitly accepting blame – in order to secure the immediate divorce that, in most cases, both of them want.

The process goes so far as to involve the parties’ lawyers exchanging drafts of proposed catalogues of transgressions with the intention of producing a list of offences sufficiently serious to convince a court of unreasonable behaviour but not so egregious that it makes it too difficult for the “guilty” party to acquiesce in the tarnishing of their own reputation.

In the recent English case of Owens v Owens, Sir James Munby in the Court of Appeal expressed the view that this situation, a consequence of the legal requirement to attribute blame, was based on “hypocrisy and lack of intellectual honesty”. Sir James indicated his support for a change in the law and the introduction of a no-fault system, adding his voice to a growing campaign which may see legislation introduced in the UK parliament in due course.

The Redknapps

Naturally, in the case of the Redknapps’ divorce, the media have focused on Louise’s allegation that Jamie has behaved unreasonably and that, as a result of this behaviour, she “cannot reasonably be expected to live with him”. Some, perhaps dubious, sources apparently consulted by The Sun – so-called “pals” of Jamies – have said that he was “furious” at being blamed in the petition but decided nevertheless not to dispute the terms as he wanted the matter finished without undue delay. Whatever the provenance of The Sun’s sources, all this would seem par for the course in terms of divorce proceedings in England and Wales. One party makes the petition alleging unreasonable behaviour and cites various examples. The responding party, though unlikely to be overjoyed at being the subject of such accusations – and not necessarily accepting the truth of them – does not contest the divorce in order to have the process concluded as quickly as possible. It is likely that Jamie, on legal advice, decided to take a pragmatic approach and avoid a contested divorce involving extended adverse publicity and, of course, increased legal costs. He chose, it would seem, the lesser of two evils.

The grounds for divorce in Ireland

In contrast to the situation in England and Wales, Ireland has a “no-fault divorce” regime.* Nevertheless, from the point of view of couples who no longer wish to be married to each other and want to obtain a quick clean break, the position in this jurisdiction is hardly much better. There is no provision at all in Irish legislation for a couple to be granted a divorce – notwithstanding their mutual consent and the fact that their marriage has irretrievably broken down – unless they can show that they have been living separate and apart for four of the last five years.

So, from the point of view of couples who have decided they want to divorce and want to do it quickly, the legal position in both England and Ireland is far from satisfactory. In one jurisdiction a couple is often forced into an undignified charade of accusation and blame-taking; in the other they must simply wait and deal with all the unhappy consequences of artificially extending a marriage long past the time it has, to all intents and purposes, come to an end.

On a positive note, it looks like Ireland will have the chance to resolve the problem for couples such as these in 2018. The government has decided to proceed with a referendum (as required by the Constitution) to reduce the time a couple must have spent living apart to two out of the last three years, rather than four out of the last five. So far, no specific date has been set for the referendum.

We will await developments.

*It should be noted that the grounds for Judicial Separation in Ireland are different to those for divorce and are in some respects analogous to the legal requirements for divorce in England and Wales, in that they include adultery and unreasonable behaviour as well as periods of living apart and desertion.

So, from the point of view of couples who have decided they want to divorce and want to do it quickly, the legal position in both England and Ireland is far from satisfactory. In one jurisdiction a couple is often forced into an undignified charade of accusation and blame-taking; in the other they must simply wait and deal with all the unhappy consequences of artificially extending a marriage long past the time it has, to all intents and purposes, come to an end.

On a positive note, it looks like Ireland will have the chance to resolve the problem for couples such as these in 2018. The government has decided to proceed with a referendum (as required by the Constitution) to reduce the time a couple must have spent living apart to two out of the last three years, rather than four out of the last five. So far, no specific date has been set for the referendum.

We will await developments.

*It should be noted that the grounds for Judicial Separation in Ireland are different to those for divorce and are in some respects analogous to the legal requirements for divorce in England and Wales, in that they include adultery and unreasonable behaviour as well as periods of living apart and desertion.